Sunday, December 31, 2017

Eat Gay Love

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Alien v Predator

|

| Whoever wins, we lose. |

|

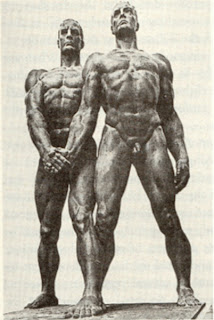

| "Comradeship" by Josef Thorak |

|

| Though not for lack of trying, I'm sure. |

Monday, July 13, 2015

All the Feels

Therein lies the brilliance of the conceit at the heart of the movie. Everything of consequence that happens within Riley's mind--the crumbling of her personality islands, the irretrievable loss of memories--is part of its working order. To stop working, Riley would have to be brain-dead; she still functions without her core memories, but in increasingly dysfunctional ways that become self-destructive. The moment when the control panel starts greying over and the emotions can't control it is a refreshingly lucid depiction of depression as not mere sadness, but the inability to feel emotions of any kind--but it's an 'aha' moment for a first-time viewer that this is in fact a story about depression, or at least the potential for it without a healthy exercising of one's emotions.

It is only after surveying the story as a whole that the theme of depression comes into full view. For what is depression but the mind turned against itself, marshaling its analytical and emotional power towards self-flagellation and eventual self-destruction? And what is going on inside Riley's brain but that her inner workings are working against themselves? Thus do we return to the issue of an antagonist: if Riley's brain is the protagonist of the story, working to keep her well-adjusted and healthy, it is also its own opponent, spiraling into lethargic depression when its attempts to stay relentlessly happy fail. A depressed person is their own worst enemy.

And that is why Pixar are geniuses.

Saturday, February 21, 2015

Oscar Predictions

Those in the 'Should Win' category marked with an asterisk were not nominated. Seriously, Gone Girl got screwed.

BEST PICTURE

Will win: Boyhood

Should win: Boyhood

LEAD ACTOR

Will win: Eddie Redmayne

Should win: Michael Keaton, Timothy Spall*

LEAD ACTRESS

Will win: Julianne Moore

Should win: Rosamund Pike

SUPPORTING ACTOR

Will win: J.K. Simmons

Should win: Edward Norton, Ethan Hawke

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

Will win: Patricia Arquette

Should win: Patricia Arquette

ANIMATED FEATURE

Will win: How to Train Your Dragon 2

Should win: The Lego Movie*

CINEMATOGRAPHY

Will win: Birdman

Should win: Birdman, Mr. Turner

COSTUME DESIGN

Will win: The Grand Budapest Hotel

Should win: The Grand Budapest Hotel

DIRECTING

Will win: Boyhood

Should win: Boyhood

DOCUMENTARY FEATURE

Will win: Citizenfour

Should win: Citizenfour

DOCUMENTARY SHORT

Will win: Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1

Should win: Don't know

EDITING

Will win: Boyhood

Should win: Gone Girl*

FOREIGN LANGUAGE FILM

Will win: Ida

Should win: Don't know

MAKEUP AND HAIRSTYLING

Will win: The Grand Budapest Hotel

Should win: The Grand Budapest Hotel

ORIGINAL SCORE

Will win: The Theory of Everything

Should win: Interstellar, Gone Girl*

ORIGINAL SONG

Will win: "Glory" from Selma

Should win: "Glory" from Selma

PRODUCTION DESIGN

Will win: The Grand Budapest Hotel

Should win: The Grand Budapest Hotel, Interstellar

ANIMATED SHORT

Will win: Feast

Should win: Feast

LIVE ACTION SHORT

Will win: Parvaneh

Should win: Don't know

SOUND EDITING

Will win: American Sniper

Should win: Interstellar

SOUND MIXING

Will win: American Sniper

Should win: Birdman

VISUAL EFFECTS

Will win: Interstellar

Should win: Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

ADAPTED SCREENPLAY

Will win: The Theory of Everything

Should win: Gone Girl*

ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY

Will win: Birdman

Should win: Birdman

A Brief History of Time-Spanning Biopics

To try to fit an entire life into a feature-length movie is impossible, so the question of how to deal with figures whose life stories are so well known becomes a matter of focus. There are, generally speaking, two extremes:

1. Focus on a single goal or event, to illustrate the essence of the figure in question, at least during the time depicted.

2. Try to get as many incidents and anecdotes in as possible, the better to illustrate the events that shaped the person into who she became.

The first approach is generally the more successful, as it is the approach taken to most non-biopic films: introduce the character, give him a goal, and make him work for it. All of the normal storytelling principles of character creation, cause-and-effect narrative, tension and release, are here observed. Selma sticks to this approach and is the better of most of its fellow contenders for it. By focusing on the events in its titular city over the course of a single summer, it allows us to see the nuts and bolts of Martin Luther King Jr.'s doctrine of non-violence: the background of the city and the country's racial conflict, the stakes involved, the planning and arguments and doubts, the setbacks, the eventual triumph. Through this we see many sides of King--brilliant orator, shrewd strategist, shamed adulterer--that are obscured in the popular imagination. They would certainly be obscured in a survey of his 'greatest hits' that the conventional biopic form would dictate.

The second method is more perilous, but also more often deployed. The fact of the characters being real, and real famous, tends to overwhelm the needs of the script, and so too often these movies become a bland series of Big Events that often bear little relation to each other. This happens, then that happens, for two hours or more. Development of characters tends to be thin, because their circumstances are changing so quickly that we don't have time to get a sense of who they are and what they are dealing with in any given moment. It's ultimately self-defeating--in an attempt to show us everything about a person's life, we learn little about who they are.

This is the damning problem with the wildly over-hyped The Theory of Everything: the movie crams into two hours Stephen Hawking's rise as a celebrated physicist; the deterioration of his motor facilities; and the beginning and end of the relationship with his first wife Jane Wilde, across several decades. None of these three subjects are explored in any real depth, nor are the characters: Stephen Hawking becomes a standard suffering genius, and Jane is flattened into a saintly doting wife (except when historical necessity requires she begin to have doubts and frustrations). The Imitation Game too subscribes to this model, with predictably disastrous results. Besides its condescending treatment of its subject's sexuality, one of its worst narrative sins is splitting the difference on the story it's trying to tell: World War II code-breaking on the hand, post-war persecution by the British government on the other, with a tragic boyhood romance thrown in for bad measure. None of it sticks, except for a sequence near the end that deals with the actual procedural details of cracking the Germans' code, and having to grapple with the cost in lives of not being able to reveal their discovery. More is less.

On a script level it's difficult-to-impossible to mitigate the drawbacks of the kitchen-sink approach, but it is possible for the direction of the movie to do so. A director can use the movie's mise en scene to depict the world as seen through the eyes of its famous subject. This is the tack taken by the criminally under-appreciated Mr. Turner, which marshals its gorgeous cinematography toward recreating the awesome English vistas that J.M.W. Turner painted. It also widely sidesteps the trap of trying to create a Lifelong Arc by both confining itself to the artist's later years, and also drifting through the years ala Boyhood. This allows us to see the man naturally, in a variety of often mundane everyday moments, rather than lashing together a number of plot points in service of a forcedly tidy narrative.

Selma has some formal audacity, albeit of a very different kind. It reinvigorates the tired device of superimposed titles used to tell the audience the when and where of a scene, by styling them as FBI surveillance notes. In doing so it illustrates the extent to which King was monitored, and also occasionally creates a dissonant note between what is presented and how it is described--the use of a term like "Negro agitator" speaks volumes about how the Civil Rights Movement was viewed. The movie also makes smart use of its music, juxtaposing cathartic African-American spirituals with the brutality of the police crackdowns depicted onscreen, and featuring an end credits song, "Glory," that draws explicit lines between the events of the film and the protests that erupted in Ferguson, Missouri during its production.

Whichever the approach taken, the question of accuracy will always hang over a biopic. Strict fidelity to the facts is ultimately a straightjacket: life is messy and redundant and full of too many peripheral figures to count; narratives, especially in a medium that with a fixed length like cinema, demand an economy not found in real life. Questions of absolute accuracy should come second to dramatic needs.

The key is to remain true to the spirit of the figure in question--portray them as the kind of person they were, in the kinds of situations they faced. One of Selma's weakest aspects is its one-dimensional portrayal of George Wallace as an unremarkably hissable old racist when he was in fact a cynical strategist, summoning the demon of Southern racism in a Faustian bid for votes. A less pernicious lie has Correta Scott King confronting her husband with an audio tape of him having sex with another woman, a tape furnished by the FBI. This never happened, but it is forgivable because of the broader truths it is illustrating: the FBI's invasive and illegal surveillance of King, and the marital strains, of his own making, which he faced. As the old maxim goes, never let facts get in the way of the truth.

Of all the prestige biopics to ignore this guideline, American Sniper is the most egregious. It portrays Chris Kyle as ambivalent about his 'Deadliest Sniper' reputation, not necessarily proud of what he does but grimly determined to see his work through to the end. The real Kyle was in fact proud of his distinction, going so far as to rack up a few extra kills in order to keep ahead of any would-be challengers. He was also wildly boastful, to the point that he invented stories about punching out Jesse Ventura and sniping looters from the Superdome during Hurricane Katrina. American Sniper is solid if mostly unexceptional as a film, but by completely ignoring these fundamental aspects of his character--the contradictions of which would make for a fascinating story in themselves--it fails utterly as a biopic. For Clint Eastwood, the truth was an obstacle to his fiction.

The Academy attention showered on The Theory of Everything, The Imitation Game, and American Sniper, and the snubbing of Selma and Mr. Turner, bespeaks not just a political and social conservatism, but aesthetic conservatism. The filmmaking of the former is reliable at best, tired and dull and misleading at worst; the two latter films are not perfect (Selma is occasionally hobbled by punch-you-on-the-nose dialogue, and Mr. Turner does run awfully long), but they, in their own ways, are doing pushing the medium in exciting directions and doing good by their subjects. For biopics that have aspirations beyond Oscar-bait they serve as excellent models.

Friday, January 16, 2015

Pale Imitation

The movie acts coy about Turing being gay, with a cop at the beginning of the movie looking at the camera and saying, "I think Mister Turing has something to hide!" and then waiting until halfway through the movie to "reveal" that he's gay. This is made worse by an obnoxious subplot that takes place in Turing's schoolboy years that makes his boy love abundantly clear and serves no other purpose but to do so. The movie spends half of its runtime on a bullshit 'prickly genius needs to learn how to get along with people' plot that was far more effectively done in The Social Network, comes alive for twenty minutes or so with some actual code-breaking and discussion about the ethics of keeping their knowledge a secret, and then, finally, gets into the British government's prosecution and persecution of him. But then it merely talks about his trial and conviction, and then glosses over his suicide with some end titles. This, after tossing in a rancid joke about cyanide--his method of suicide--in that awful opening scene.

The movie wants to make some big statement about how shoddily the British government treated a national hero based on his sexuality, but ends up treating his sexuality, and his heroism, shoddily in turn. I've heard of form fitting content, but this is fucking ridiculous. That it's being nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay is a travesty of art and gay politics.

Saturday, November 8, 2014

Intergalactic Planetary

The Setup: In the near future, Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) was a NASA pilot once, but now spends his days tending a farm, raising what crops he can with his two children Murphy (Mackenzie Foy, later Jessica Chastain) and Tom (Timothée Chalamet, later Casey Affleck) with his father in-law Donald (John Lithgow). The earth is subject to frequent dust storms and blight that is steadily wiping out entire crop species, and the Coopers seem to be at the center of some strange magnetic forces that lead them to a secret NASA base led by Cooper's old mentor Professor Brand (Michael Caine) that's planning to evacuate humanity from the Earth, which requires finding a habitable planet to colonize, which in turn requires making contact with members of the exploratory team, including one whose identity I won't spoil, that was already sent out. Cooper arrives just in time to pilot this expedition, with a team that includes Brand's daughter Amelia (Ann Hathaway) and a personable robot assistant, TARS (Bill Irwin), who is so much less annoying than it could have been. To everyone's surprise things do not go as expected.

Simple, no? No elaborate mechanics of dream extraction nor unwieldy conspiracies to unravel, just a straightforward tale of setting out to do a big thing or two to save the world. There are complications along the way, and a few Big Questions that the plot is going to eventually solve, but the answers (in the broad sense if not their weird details) are kind of obvious, and once it gets going the film becomes mostly concerned with wowing the audience visually, when it's not lecturing them about love (and sometimes even when it is!).

That's once it gets going: the first act is an odd beast, with character-building exercises that function to set up later plot developments for both this movie, and one that doesn't exist (I have no idea what to do with the knowledge of Cooper's cancer-killed wife, and neither does the film). On the plus side, its world-building is refreshingly unfussy. The blight crisis is spelled out in no uncertain terms, but the implications that it's had for society--which has apparently shrunk so drastically that the crowd size for a New York Yankees game is appropriate for a Little League match--is understated. The film doesn't know how to transition out of this into space exploration mode, though, at all, so it more or less cuts to liftoff rather gracelessly. It feels like a whole act has been sliced out of the movie, but I cannot imagine anything of importance being included in it and am grateful that the movie is not longer than its epic two hours and forty-five minutes.

Once we're off to the (space) races, the movie Interstellar most brings to mind is Danny Boyle's Sunshine, both in its 'last-ditch mission to save humanity' setup, and also its abrupt third-act shift out of an unhurried storytelling mode into tension and white-hot action. The difference, though, is galactic: for where Sunshine has an unimpeachably brilliant build-up that is thrown away for hectic film-breaking bullshit, Interstellar's extended dual climaxes save it from the insubstantial naval-gazing that has come before. There so much talk, about love as a force like gravity, and there is so, so much crying. It is not without reason, certainly, but it is an emotional cheat. Even with Nolan's usual plot knottiness stripped back the characters still feel like devices rather than people with interior lives that we are privy to, and so the weepiness has little impact.

Nolan is on much surer footing when he's trying to knock our socks off, which he does spectacularly and often. The images (which I saw in glorious IMAX 70mm film projection) are rich and frequently mind-bending, and they're paired with some choice sound design. There's a moment where a shot of a shuttle orbiting Saturn is juxtaposed with the sound of rainfall and thunder that approaches sublimity, and the success of the movie's third act that I mentioned is largely owed to the sturm und drang of Hans Zimmer's hulking score, which over a sustained half hour mutates from strings into pipe organ into electronics, building and releasing tension masterfully.

With much of this approach, it seems Nolan wants more than anything to recall the heady sci-fi of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. He comes close in parts, especially the climax of the climax, but he is hamstrung by his (and his brother Jonathan Nolan, with whom he wrote the script) insistence that everything make narrative and logical sense in the end. 2001's success rests entirely on matching its unforgettable visuals with elliptical storytelling that leaves much unexplained and invites the viewer to provide meaning. Nolan's got the visuals down pat, but he tells us everything (including when to cry) to considerably diminished effect.

It didn't have to be this way; Inception's dream logic was undermined by a similar heavy-handedness, but The Dark Knight used its very messy structure--which would normally be a liability--to formalize the story it was telling: it made the audience feel the Joker was an agent of chaos, rather than just telling them. Interstellar falls short of its lofty ambitions, much as Inception did, but it's still very entertaining and awe-inspiring on its own terms. It shows Nolan loosening up, perhaps too much in the waterworks department, but it's a welcome development all the same, and the craftsmanship is as impeccable as ever.

Friday, May 16, 2014

Notes on Godzilla

Because it's quicker than an essay.

- The opening credits are the best I have seen in years, since Watchmen at least. Big, exciting music set to blocks of classified text that are swiftly redacted leaving only the cast and crew, all superimposed over "stock" footage that I only realized toward the end was in fact giving us a condensed version of the movie's Godzilla's origin...

- ...which it strangely elects not to tell. There's sentimental value in having had him originally make trouble in 1954 and only now reawaken, but beyond that...why? The film never really explains why he's around and has it out for these giant bugs that are the real enemy. This is a reboot if anything, and though superhero origin stories are by now well-worn, it would have been interesting for the humans in the film to treat Godzilla as a force of nature rather never before encountered than to be largely taken for granted. A big part of characterization, even of characters who only roar at things, has to do with how they are regarded by the other characters; having Godzilla be treated as not that big a deal, makes him not that big a deal.

- The biology of those giant bugs makes no sense. They are originally introduced as parasites, discovered inside the fossilized remains of a giant...something. But their whole mission in the movie is to incest mate, in some hole in the ground. If anything they should be trying to fuck each other through Godzilla, which would certainly give the movie the horror kick that monsters seem to lack these days.

- The humans' strategy doesn't make much sense either. If you're trying to get a nuclear bomb past the baddie that we know doesn't fly, why send it on a train to be attacked, and then airlift it? (Because a train attack looks cool, of course, and I'll admit, the shots of the female bug passing over and under and around the bridge are pretty neat.)

- I like the Godzilla design. Much good use is made of the dorsal fins, cutting through the surface of the ocean like a shark times a million, and the face, while strangely dog-like in its nose, is quite expressive. He's got a nice 'fuck you' sneer to these giant bugs.

HERE BE SPOILERS

- I guess this is the closest I'll come to knowing what it felt like to watch Psycho when it first came out, because I was genuinely shocked that they killed Bryan Cranston not even halfway into the movie. It's a bold gambit, but it doesn't pay off because there's no Anthony Perkins to replace his Janet Leigh. The ostensible star of the movie, the big lizard, is deliberately only glimpsed through much of the film to keep from spoiling his mystique. Which is all well and good, but that leaves us with the other humans, none of which step into the celebrity void to anchor the film that Cranston leaves behind him. Ken Watanabe has the most natural gravity, and I was hoping that Cranston's death would clear the way for the story, such as it is, to focus on a character who is actually from the nation that gave us Godzilla. But Watanabe is reduced to spouting pseudo-profundities about Godzilla 'creating balance' and man trying to control nature. After being introduced as the leader of the lab that's been keeping the bug egg a secret for a decade-and-a-half, he ends up having nothing to offer and unlike Cranston isn't allowed to die when he's outlived his usefulness. Aaron Taylor-Johnson instead becomes our ostensible lead, but he is no more memorable than whatshisface from Pacific Rim was. None of the characters are so stock-y, but neither are they compelling in their own right either.

- Pacific Rim was dumb by design, and its humans generic ciphers. Godzilla tries to put some meat on these bones, the better to give some weight to the events at hand. The scenes have a greater visceral thrill by giving us so much of a worms-eye view of the destruction, but the consequential violence is all front-loaded, and none of the characters matter enough anyway. And there's some good monster action to be had, including some applause-baiting money shots. But the movie's coy approach to its monster star and undue emphasis on its human stars eventually works against it by cutting away from its final battle to characters who have long since ceased to be interesting.

- So the human : monster ratio in these movies has yet to be perfected. Godzilla is probably the better film, but I can't help but wonder if Pacific Rim is the better monster movie.

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Driving Each Other Crazy

The proceedings start strong with “Bench Seat.” Two young lovers (Emma Thorne, Logan Sutherland) are up on a secluded hillside overlooking town to make out, or, maybe, to break up, as it becomes clear that the young lady has serious, serious issues. The piece is a neat study in contrasts, with Sutherland’s smooth jocularity (which eventually shades into a passive resignation) juxtaposed with Thorne’s jagged, twitchy paranoia. Like several of the pieces it goes on for too long, circling back to the same topics and comic devices, but the performers’ energy never flags and it entertains and unnerves in equal measure.

Said energy carries over to the next playlet, the best of them, “All Apologies.” It is a comic monologue, given by a man (Jonathan Berenson) to his wife (Jill Durso), in which he apologizes in his own fashion for being an abusive sack of shit. It flips the dynamic of the previous scene, with the woman now reacting, this time silently but so intently, to the increasingly unhinged man. His rambling is a tour-de-force performance in bullshit-spinning peppered with digressions on the origin and meaning of words like “awesome” and “golf,” in the end punctured simply and devastatingly by the wife’s incredulous laughter. The laugh is not in fact in LaBute’s script--she merely stares instead--but it’s a welcome addition that opens the storytelling perspective beyond the captivating and entertaining monster at the piece’s center and keeps it from letting him off the hook.

The same, alas, cannot be said for “Merge,” in which a husband (Anthony Taylor), having picking his wife (Haley Palmaer) up from a convention, tries to parse her ambiguous testimony about having been raped in her hotel room. She wasn’t raped, we learn, for she drunkenly invited all those/both those (the use of the word ‘all’ is a detail the husband clamps onto with the tenacity of a pit bull) men to join her. The script’s one-sidedness--we never get an explanation for or exploration of her nymphomania--makes the play problematic to begin with. Coupled with Anthony Taylor’s furious, accusatory take on his character, it makes the play an ugly exercise in slut-shaming which reaches its terminal conclusion in a nihilistic ending, a murder-suicide traffic swerve that is merely hinted at in the title and stage directions. Of the night’s proceedings, it’s a considerable bump in the road.

The show gets stuck in second gear for the the next piece, “Road Trip.” We’re presented a man (Todd Litzinger) and a young girl (Caroline Jordan) on a seemingly innocuous excursion. We learn that he’s a predator, and like most predators he’s family or something like it, probably her step-father, and this trip, for the girl at least, is decidedly one-way. The relationship between the two characters and the reveal of its true horrible nature is drawn delicately, but the tension of the play exists only between the audience's omniscience, and the limited perspective of the girl. Between the girl and the man there isn’t so much friction, and the piece never quite takes off because of it.

Though it shares similar subject matter, this is not true of the final and most intriguing piece, the show’s namesake, “Autobahn.” Like “All Apologies” it’s a monologue, this time given by the woman (Annie Grier) ruminating while her husband (Jonathan West) drives, about their troubled foster son’s accusations of sexual abuse. The play rightly doesn’t belabor the reveal of what it’s about and so spends its time exploring the two characters’ responses to this situation and, accordingly, forcing us to wonder what exactly the situation is. The wife’s chatter, her rationalizations and can-do optimism, increasingly feel like an evasion of a horrible truth. Meanwhile Jonathan West wears a mask of the most profound sadness--but is it a mask? Is it guilt? Self-pity? Manipulation? The play never tips its hand in either direction. This can be frustrating, playing up an ambiguity for which, as Dylan Farrow’s recently renewed allegations against Woody Allen have shown, there is no luxury in real life. As a work of drama, though, the did-he-or-didn’t-he question works, especially as a contrast to the other the earlier plays, whose creeps we were allowed to feel much more certain about.

The production, it should be noted, eliminates two of the seven vignettes, "Funny" and "Long Division." They are missed not for the plays in themselves, though "Funny" is quite good, but for their casts, two women and two men; the one man-one woman dynamic of the other plays, especially given Neil LaBute’s fixation on abusive sexual relationships, could use some variety. What we are given, however, is a solid offering, directed and performed with energy and attention, in service of an at-times uneven collection of plays. As a vehicle for drama, the engine occasionally threatens to stall, but the body is ever polished.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Once More, With Feeling

Saturday, January 12, 2013

More is Les

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Pun Nintend(o)ed

(Some spoilers follow.)

Wreck-It Ralph should be viewed as less a movie than a cultural artifact of the early 21st century. It is not a bad movie, by any means. Its construction is sound, its technical ability accomplished, its celebrity voice casting surprisingly successful (I typically find Sarah Silverman grating, but here, no longer able to just be as obviously "offensive" as possible, she is refreshingly spunky). On entertainment grounds, it is largely successful. But far more interesting than how funny it is (quite, and quite often), is the way it trades on its audience's knowledge of video games, and depends on video game characters and iconography for its effect. So completely reliant is it that, regardless of its merits as popcorn cinema, it functions less as an independent cultural entity than as a milestone in postmodern cross-corporate artistry.

The contours of the story are deceptively familiar. In the games of Litwak's Arcade, all the characters live in a world unto themselves. The villain of Fix-It Felix Jr., Wreck-It Ralph (John C. Reilly) spends his days smashing windows that Felix (Jack McBrayer) repairs in order to eventually save the building's tenants, who throw Ralph off the building at the end. Tired of always being the villain and having to live in the dump, Ralph abandons his game one day to try to win a Hero's Medal in alien invasion first-person shooter Hero's Duty. In doing so, he crash lands in a candy-themed racing game called Sugar Rush, bringing with him one of the nasty, reproducing bugs from Hero's Duty. In the process he raises the ire of Sugar Rush's King Candy (Alan Tudyk) and Hero's Duty Sergeant Tamora Calhoun (Jane Lynch). He then enlists glitchy exiled racer Vanellope von Schweetz (Silverman), to win him a medal in a race so he can get back to his own game before the arcade owner decides it's irreparably out of order without him and has it unplugged and taken away.

The scenario is classic Pixar, even though this is a Disney film. Toy Story was about the secret world of toys, A Bug's Life the secret world of bugs, Monsters, Inc....You get the picture. Yet rather than these films, Wreck-It Ralph shares a far stronger kinship with Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, a film which also used the storytelling grammar and tropes of video games to an unprecedented degree, but even then just as a filter for an otherwise grounded love story. Ralph is about video games, period, and to its end enlists an array of cameos spanning the past thirty years of video games, from Q*bert to Pac Man to Street Fighter to Sonic the Hedgehog to Super Mario Brothers and beyond, with homages to other games not mentioned by name. To understand the difference between this and the Pixar pictures, imagine if, rather than just Mr. Potato Head and Etch-a-Sketch, Andy's room in Toy Story was populated with Stretch Armstrong, Transformers, G.I. Joe, He-Man, and other such brand names. That would have been distracting at best--but here it's vital, not just to the world of the movie, but also to its humor and themes.

Nor is it simply a crass toy commercial, not the way the actual Transformers cartoon was all those years ago, but neither is it a self-contained product. A look into the 'universe' of video games would simply not be convincing without being populated by authentic video game characters, every one of them worth millions of dollars and owned by media giants. A good case could be made that 20 years after Super Mario Brothers: The Movie, the reason there are no great films based directly on a video game is that the characters are too tied to the companies that own them, and they exist solely to sell products, the games themselves, that make those companies money.

And it's not just characters that are being licensed here. An assortment of brand names appear, in all manner of capacities. A close-up shot of a Subway cup is the most blatant and annoying; embedded far deeper in the movie's being are Oreos, which are the subject of a gigglingly obvious Wizard of Oz pun, and Mentos and "Diet Cola," on which a training montage and the movie's climactic action scene are inextricably tied. As with the game characters, the product-placement so completely sublimates the mise en scene that the two become bound, the art as vehicle for the ad, the ad as vehicle for the art.

It's all very entertaining, in the way that inside jokes are very entertaining to knowing insiders. (The movie is rotten with delicious candy-themed puns, which are the lowest of inside jokes, in that you only need to understand the language to understand the joke.) I'm not so much of a scrooge that I didn't enjoy myself. But still, should we not be a little depressed that every new character worth dressing up as for Halloween is now owned by some soulless mega-conglomerate?

The old criticism of Disney was that it debased classic stories and characters by reducing them to commodities. Yet in order to turn the little mermaid Ariel into a marketable Disney princess, the House of Mouse still had to create their own engaging version of a character that had existed in numerous, independently-created iterations for over 150 years. Copyright laws and media consolidation have so strangled our cultural development that our classics today are commodities, which exist and are licensed only in approved forms and tended with an eye for the bottom line. By modern laws and logic, everything that followed Hans Christian Andersen's Little Mermaid was either intellectual property theft, or fan-fiction.

The fact of this creative corporatism--or is it corporate creativity?--affects not just the film's storytelling but also its message. By focusing and placing audience sympathies on Ralph, a "villain" who wants to be good, it presents itself as an underdog story of rebellion against a prevailing order. (Tellingly, Ralph resolves to do this in a funny scene set at an AA-styled meeting for video game villains that includes original rebel, Satan himself.) Yet games, the film's creators cannily understand, operate by rules that dictate what does and does not happen in a digital world. That's what video games are, essentially: programs made up of millions of lines of code that act as pure logic. It's a very conservative way of looking at the world that in this case happens to be true: the rules, the code, can't be changed. Thus Ralph's attempts to be a hero in the way Felix is, are doomed to fail (the code for Sugar Rush is changed as part of the machinations of the villain, a notably arbitrary plot device that is out of step with much of the rest of the film). When it comes to his world, the world of Fix-It Felix Jr., Felix will always be the hero, and Ralph will always be the villain.

One can read into this a certain reactionary strain of thinking that says things can never truly change, that the discontented ought to just be happy the prevailing order and get on with it, lest they destroy everything. It's certainly befitting a top-down hierarchical corporation with more money than God. Yet one can also hear in Ralph's final lines, in which he says that the best part of his day is just before he is thrown off the building, because it is then that he has the highest, greatest view of the arcade--one can hear in it echoes of The Myth of Sisyphus (indeed, is there anything more Sisyphean than living life according to a 'reset' button?):

I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.One must imagine Wreck-It Ralph happy.

Like The Dark Knight Rises earlier this summer, Ralph tries to split the difference in its dealing with change and the status quo--for it is not just the villains but the heroes that must live by this code (there's that word again...). Towards the end of the movie, we learn that King Candy is in fact the hero of a previous racing game, Turbo Time, who grew jealous of a new racing game that took players away from him. He invaded the game and glitched it, causing both his game and the new one to be unplugged. He then secretly installed himself in Sugar Rush and overthrew Vanellope, its queen. The putative hero was subject to the same rigid system as Ralph, a "villain." Not coincidentally is Vanellope restored to her throne, whereafter she renounces her crown in favor of "constitutional democracy," a term I'm fairly certain has never been used in a Disney animated movie until now. Democracy, of course, is the quintessence of 'splitting the difference,' which seems to be the essence of the message the film is trying to impart. America's brand of democracy today goes hand-in-hand with the kind of pervasively entrenched corporatism I was talking about earlier, and so the circle is complete: corporate art encourages corporate democracy encourages corporate art.

Wreck-It Ralph is thus as much about its own nature as a vehicle of the postmodern zeitgeist, as it is about video games and how they drive the zeitgeist itself. I hasten to add that this postmodernism, this collapsing and subverting of the old definitions, cuts both ways. It's not just that rather than art becoming commercialized, our commercials are becoming art. Twenty years ago, my seven year-old self was allowed to watch Disney movies but not to rip someone's heart out of their chest in Mortal Kombat. Now a Disney movie marketed to seven year-olds includes a scene with Mortal Kombat baddie Kano ripping the heart out of a zombie. It's very funny in the context of the movie, but broadly speaking, not so much. Game Over, man.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Golden Fleecing

Recent history gives Argo's opening scenes an especially visceral immediacy. Cutting archival footage of the 1979 storming of the American embassy with period perfect re-enactments, and depicting attempts within the embassy offices to deal with the rapidly escalating situation, the sequence has a terrific on-the-ground quality that starts the movie off with bang. By so vividly recreating the events of '79, it provides an uneasy vicarious experience of the Egyptian and Libyan missions of but a month ago. (I don't know if Warner Brothers ever considered delaying the movie's release out of "sensitivity" regarding the Libya attack, but since such moves are stupid and self-defeating, I'm quite glad they did not.)

After six American diplomats manage to escape and find asylum in the home of Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor (Victor Garber), the movie settles into what is essentially a heist flick mold. Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck), CIA rescue ops badass, is tapped by State Department mover and shaker Jack O'Donnell (Bryan Cranston) to figure out how to rescue the six Americans. He eventually settles on a plan, "the best bad option," to enter the country posing as a Hollywood producer scouting locations for a fake Hollywood science fiction movie, and to disguise the diplomats as his production crew and take them back with him. To do this he needs to create a believable dummy production--including script, concept art, and authentic trade magazine publicity--with the help of Planet of the Apes makeup man John Chambers (John Goodman) and producer Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin). Which is hard enough before having to actually go to Tehran and get the Americans out before the sweatshop workers piecing together their shredded embassy photos can alert the Revolutionary Guards that there are Americans hiding in Tehran.

The plot pretty much takes care of itself, explaining the steps to be followed and then upping the ante with a raft of complications along the way. It's solid stuff, and the script and actors deftly balance the grave seriousness of the problem with the absurdity of the solution at hand. The good humor of Arkin and Goodman (who at one point tells Affleck, who directed this movie, that you "can train a rhesus monkey to direct in a day") dominates the Hollywood-heavy first half, somewhat to the detriment of the back end. As they can only sit around and wait to be rescued, the American hideaways are only given the barest of character development, and so it falls mostly on Affleck to carry the picture once it moves to Iran. He does good work as the smartest man in the room, steely and unflappable except for a concern about having to be away from his family that is exactly as perfunctory as it needs to be. Still, it would have been nice to get to know the trapped Americans better in order to contrast them with the roles they are forced to adopt for their survival.

Without getting into too much detail, the movie's third act goes perhaps too far in the use of creative license. The action got to be enough that it took me out of the film, and I started to wonder how much of this was true. It's not a fair complaint--there really was a lot that was fictionalized, to the movie's benefit--and William Goldenberg's editing does wonders tying together three plot threads that moment-by-moment push the tension ever higher. But the movie does start to feel (ironically?) a little too Hollywoody, whereas everything that came before was believable and restrained.

Maybe it's just recent events, the "too soon" factor, that make me fault the movie for its drift into fancy. If so, it works more than one-way. For not only does the September 11 consulate attack shape the way one approaches Argo, but Argo shapes the way one looks at the consulate attacks. It isn't much of a spoiler to say that the operation is successful but the U.S. government must publicly give all credit to the Canadians because the embassy hostages would otherwise face brutal reprisal. The movie ends here, but in the real world history marched on: those hostages and the failed attempt to free them, for whose sake the government buried the story of its most spectacular rescue mission, helped destroy Jimmy Carter's presidency, and it was not until he left office that they were freed.

Too often secrecy is invoked by our government today as a means of covering up information that would embarrass it. Argo presents an all-too-rare instance of secrecy that did precisely the opposite, that downplayed success for the greater good until 1997, when the mission was declassified. If there's a takeaway from the timing of the movie's release, it's that there is often more going on in international relations than we realize. Unknown unknowns, and all that. Moreover, the people who are involved in these hot spots, do realize what's going on. Or, at least, they know the risks. As an end-of-movie caption inform us, all of the rescued diplomats, in spite of their harrowing experience, returned to the foreign service. One imagines Ambassador Chris Stevens would have done the same.

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

Who Controls the Past, Controls the Future

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Fortune of Soldiers

Americans were not the only ones serving in Iraq.

It's a fairly obvious observation, but one that I don't recall being much considered during the darkest days of that endless war. True, we often spoke of our faithful allies, the British, but even that term 'British' itself is an elision. For, as writer Gregory Burke notes in the program for Black Watch, imported for the second time from the National Theatre of Scotland by the Shakespeare Theatre Company, "Scotland has always provided a percentage of the British Army that is disproportionate to its population size." The only time I recall Scotland entering the Iraq conversation was the public dispute between a belligerent Christopher Hitchens and Scottish MP and Saddam Hussein apologist George Galloway.

We did not think much about Scotland, much less its military class, in the context of Iraq, but they thought about Iraq, and us, at considerable length. So we find in Black Watch, an exploration of the play's namesake, a famed Scottish infantry battalion, and the outsized role it played in Iraq. The play, directed by John Tiffany, is a marvel of performance and technical skill and shows a critical moment in time from an unusual perspective. Yet a crucial component is missing: the play's original audience, without which something has been lost in translation.

The play's story moves on two tracks--an unnamed writer, ostensibly Burke, interviewing the men of the Black Watch, and the stories they tell him, of daily life and daily death in Iraq. Interspersed among the interviews and vignettes are found objects of the war: a debate between two Scottish MPs; letters from an officer to his significant other; Scottish traditionals and military tattoos. Over time the team's rude banter and idle foolery gives way to frayed nerves and boiling anger as they are worn down as much by relentless shelling and suicide bombers as by the government's decision to fold the Black Watch in with other independent regiments into a single unit.

With the exception of the lights and sound, which work in tandem to create the deafening and blinding explosions characteristic of post-Saddam Iraq, the show's technical approach is deceptively simple. The Sydney Harmon Hall's proscenium arch has been reconfigured into a stadium-styled seating that requires much of the audience to cross the stage, where they must remain until the end of the performance (the show runs a fleet two hours with no intermission). At one end of the stage is strung a curtain that triples as both projection screen and scrim, and on the other end is a hefty door. A rough frame on either side allows certain moments to be played from elevated heights. Set pieces were otherwise minimal, though a great deal of mileage is made with a mobile pool table. The costuming is authentic, both in the Watch's military garb and in their easygoing civilian pub-wear. The swift action is realized by a helping dose of misdirection so that new business is constantly materializing right under the audience's noses.

No single actor stands out among the ensemble cast, as it should be in a piece about a military unit. A few, though, are given greater prominence, particularly Robert Jack, pulling double duty as the timid writer and an abrasive Sergeant, and Ryan Fletcher, as the team's de facto leader Cammy. What most impresses about the cast is the lived-in quality of their characterizations, moving with both a young, hangdog masculine swagger and military precision. Their dialects can occasionally be difficult for the American ear to untangle, but their sheer physicality does a lot of the necessary communication for them.

And there is much to communicate. The play offers some unusual perspectives, particularly for an American audience. The Watch views us, for instance, with a mixture of appallation and admiration at our overwhelming military superiority. So goes an exchange during a four hour bombing campaign:

"This is nay fucking fighting. This is just plain old-fashioned bullying like.

"It’s good fun, though."

"Do you think?"There is too the realization that ours was far from the only nation that relaxed the standards of admission to its volunteer army in order to fully staff its ranks. Late in the play we learn that one of the characters was diagnosed depressive after his first tour and should never have even been in Iraq a second time, but all that pesky medical paperwork just happened to get lost when the military needed warm bodies.

"Aye. It’s good to be the bully."

Still, or all it has to recommend it, particularly in universal moments like these, I couldn't help but feel at some remove from the play as a whole. Theatre is a live event, with each production, to say nothing of each performance, born of given circumstances. All shows are particular, but some are more particular than others. Black Watch, both the play and this iteration of it, are very much artifacts of mid-2000s Scotland, a nation the size of South Carolina with the population of Colorado. Nor is it just a play by Scotland, but of Scotland for Scotland. The show began life as a National Theatre of Scotland production at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in an old drill hall and is saturated in a cultural shorthand--not just the dialects, but the politicians, the songs, the Black Watch itself--that could be taken for granted to forge a bond between performers and the audience that is at the heart of a live experience. Transplanting the play to one of the fanciest venues of the most powerful city in the world robs it of both its physical and cultural intimacy.

There's nothing wrong with the show. But without that full connection to the audience, it can't but feel slightly rote. All theatre, all theatre that matters, is local, and so it goes with Black Watch. As was said of another disastrous American military venture, "You weren't there, man."

_poster.jpg)